By Tricia Ebarvia and Dr. Kim Parker

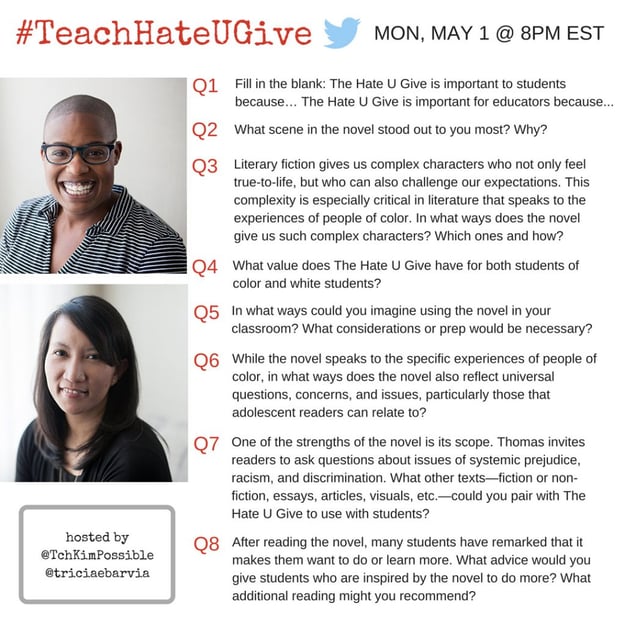

Have you read Angie Thomas’ The Hate U Give? Read on to hear our initial thoughts. Then join us on Monday, May 1, at 8 p.m. EST when we’ll be hosting a Twitter chat using the hashtag #TeachHateUGive. Scroll to the bottom of this post to preview our discussion questions.

What’s the point of having a voice if you’re gonna be silent in those moments you shouldn’t be?

—Angie Thomas, The Hate U Give

We read a lot of YA. As teachers responsible for helping shape the literacy lives of the adolescents sitting in our classrooms, like many of you, we believe that part of our responsibility to students is reading widely the books that might speak to them: who our students are now and who they might yet become. We also know the value of seeing diverse experiences in the texts we read and recommend to students. Although we both loved to read growing up, our literacy experiences were marked by a clear and glaring absence of characters of color. They simply weren’t there.

While the publishing industry has come a long way since then, the lack of people of color in children’s and young adult literature today is well documented. While people of color make up 38 percent of the U.S. population—including nearly half of all children under the age of 5—only 22 percent of children’s books include characters of color, and only 12 percent of children’s books were written or illustrated by authors of color. Furthermore, while inclusion is the first step, literature that reflects the complexities and full range of experiences of people of color remains challenging.

Which is why we knew there was something special about Angie Thomas’ debut novel, The Hate U Give.

The Hate U Give was published on February 28. Two weeks later, Tricia finished it in one day, and Kim quickly followed. After we read, we needed to do the thing that all good books demand of us—we needed to talk about it. So what did we talk about? What did we think of the novel? Below we share some of our initial thoughts:

Tricia: There’s so much to say, but I’ll start with my gut reaction. As a person of color, so many of Starr’s experiences resonated with me. I grew up as one of only a handful of other people of color, and like Starr, I find myself code-switching before I even knew there was a term for it. I loved the way Thomas captured how a person of color negotiates that “double consciousness,” as W. E. B. DuBois termed. Growing up, I was always keenly aware of being either too Asian or too white, depending on my surroundings.

Kim: Yes, I also kept thinking of DuBois’ concept of double consciousness, that people of African descent have to juggle multiple identities. DuBois described it as “twoness . . . two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings; two warring ideals in one dark body.”

I loved Starr. She reminded me of so many black girls I know and teach daily. She is complex: thoughtful, funny, beloved by her parents. I applaud Angie Thomas for giving us a well-developed black girl at this moment in time. So many black girls are depicted—erroneously—by the media as not pretty, one-dimensional, not worthy. And here is Starr! She moves between two worlds, though I worried that she had to always hide her true self when she was in her suburban school. This difficulty is not unlike what many young people might experience, particularly those who are students of color taking upper-level classes in which they are the only ones of color, or students who might be one of a few in other situations.

Tricia: I agree, Kim. I loved the way Thomas captured so many dimensions not only of Starr but also many of the supporting characters. I know that you were particularly impressed by her depiction of the male characters too.

Kim: I was struck by Maverick, Starr’s father, and broader depictions of black masculinity in the novel. Maverick, too, is a nuanced character. It would be so easy to write him off as a former drug dealer and leave it at that, but, again, Thomas is not going to let us off the hook. True, Maverick sold drugs and was incarcerated. But he also runs the only supermarket in a neglected urban neighborhood. Without his store, Garden Heights would be a food desert. With Maverick, Thomas gives us a black man who shows up for his family, for his community, and for himself.

Tricia: I also thought Carlos, Maverick’s brother-in-law, was well done. It would be too easy to make the police the antagonists in the novel, but Thomas resists that depiction with the character of Uncle Carlos, a police officer and a good man who genuinely wants to do what’s best for his neighborhood and his family. This desire is also depicted in Maverick’s choice not to move the family out of their neighborhood. He feels a responsibility to the neighborhood and asks himself: how can he make the neighborhood better if he leaves it?

Regarding Khalil, Starr’s friend who is shot early in the book—again, Thomas didn’t go for an “easy” characterization in which Khalil was undeniably innocent. Instead, Thomas allows us to walk through Starr’s own thinking—even if Khalil was involved in something illegal, even if there was something suspicious going on, he simply did not deserve to be killed. Period.

Kim: I like how you reminded us that it didn’t matter if Khalil was all of those things. Ultimately, he deserved to live. All the ways many attempted to malign him, and here’s Thomas again: his life mattered.

Tricia: The more I think about the book, the more I appreciate not only how Thomas is able to write rich characters but how much this book comments on important social justice issues.

Kim: This book is really important for helping readers understand systems of white supremacy. Why is Garden Heights as it is? More specifically, surely it wasn’t always a blighted urban community. The lack of a decent supermarket is a key indicator of so many related problems: obesity, food deserts, the process of redlining. Then, too, why is Garden Heights beset with such crime? What systematic factors are responsible?

Yet Thomas helps the reader to also see the beauty of urban areas, the roses in the concrete. After all, people live there! People flourish there! We must pay attention and acknowledge that there is so much good, so much beauty, so much resilience that gets overlooked when we are listening to headlines or buying into stereotypes.

Tricia: Too much our discourse about these issues has been reduced to sound bites. But Thomas is defiant in her refusal to succumb to those shallow understandings. She treats her characters—and these timely and important issues—with such respect and love.

I think it’s this approach of respect for her readers and love for her characters that speaks to readers. So many of my students said they loved how “relatable” the book is, even though they don’t necessarily share Starr’s background. I had the book on my classroom shelf for less than 24 hours before one of my students picked it up. She read it, loved it, passed it on to another classmate, who recommended it to a friend, and so on. I bought another copy and can’t keep either one in my classroom. This is a book that needs to be read and shared with students and their teachers everywhere.

Of course, we’d also love to hear what you think of this important book. Please join us for our Twitter chat #TeachHateUGive on Monday, May 1, at 8 p.m. EST.

♦ ♦ ♦ ♦

Tricia Ebarvia has spent the last 15 years as a classroom educator with a student-driven approach to teaching reading and writing. Through her career, Tricia has applied the philosophy of the teacher-as-researcher while applying best practices to “cultivate independent learners” through independent reading and student choice. “For better or worse, “well enough” doesn’t satisfy me. I approach each school year, each course, each unit with fresh eyes.”

Tricia Ebarvia has spent the last 15 years as a classroom educator with a student-driven approach to teaching reading and writing. Through her career, Tricia has applied the philosophy of the teacher-as-researcher while applying best practices to “cultivate independent learners” through independent reading and student choice. “For better or worse, “well enough” doesn’t satisfy me. I approach each school year, each course, each unit with fresh eyes.”

Kim Parker has worked successfully to address an achievement gap among struggling readers. She hopes her work in Cambridge helps other educators see the “potential in their historically underserved students.” Throughout her career as a teacher and through myriad leadership roles, Parker has been an advocate for classroom educators and sees her most powerful role as an educator who helps students grow their love of reading and find a book they’ll be able to connect with.

Kim Parker has worked successfully to address an achievement gap among struggling readers. She hopes her work in Cambridge helps other educators see the “potential in their historically underserved students.” Throughout her career as a teacher and through myriad leadership roles, Parker has been an advocate for classroom educators and sees her most powerful role as an educator who helps students grow their love of reading and find a book they’ll be able to connect with.