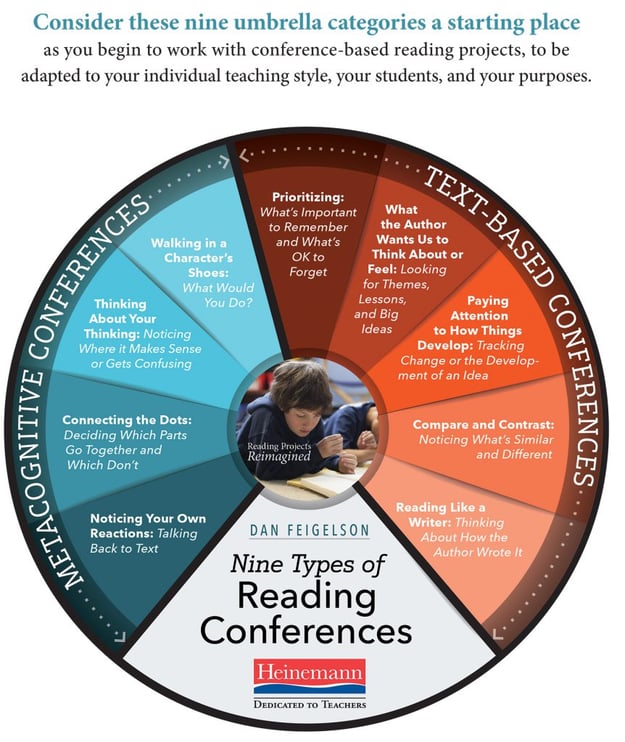

Adapted from Reading Projects Reimagined: Student-Driven Conferences to Deepen Critical Thinking by Dan Feigelson

Yetta Goodman (2002) reminds us that there are no substitutes for careful kid-watching and good listening. Nonetheless, a reading teacher can become more confident and able to adapt to students by having umbrella categories, or types of conferences, at his or her fingertips. Carving out time in the day for conference-based reading projects provides teachers with important opportunities to listen and assign readers work that is personalized and rigorous. The fundamental tenet of a conference-based reading project is that the direction should come from the student. Developing conference-based reading projects involves listening carefully to what students say about a text, and then helping them name an idea worth following.

The following nine umbrella categories are intended as a work in progress and is by no means definitive. The best use of this list would be as a jumping off point for educators to add to, revise, and refine. It’s important, always, to remember that the specifics of a good conference should come from what the individual student says and does. With that disclaimer in mind, here we go.

-

Noticing Your Own Reactions: Talking Back to Text. This is among the most basic conference types and is often appropriate for struggling readers or students who have difficulty saying anything other than “what [the book] was about.” The truth is, there are kids out there who aren’t even aware they are supposed to have a thought as they read. A “Noticing Your Own Reactions” conference is just that—paying attention to (and identifying) thoughts and feelings that cross your mind as you read.

-

Connecting the Dots: Deciding Which Parts Go Together and Which Don’t. Teaching young readers to connect the dots should start small. Sometimes it’s things on the same page that go together and make a reader say “a-ha.” As texts become more complex, a reader must make connections across many pages. A Connecting the Dots conference may be simple or complex; either way, it addresses one of the most fundamental comprehension strategies.

-

Thinking About Your Thinking: Noticing Where it Makes Sense of Gets Confusing. It’s critical for readers to have a repertoire of “fix-it” strategies to repair comprehension when something is difficult to understand (Keene and Zimmermann 1997). But before we can even go there, we must teach children to notice when something doesn’t make sense, and think about exactly why it is confusing.

-

Walking in A Character’s Shoes: What Would You Do? Not all text-to-self connections are created equal. When a child is reading Sounder or Old Yeller, to say “My grandmother has a dog” may be a text-to-self connection, but it doesn’t really help in understanding the book. When we teach students to make personal connections, it’s critical to also teach them to make decisions about which connections help us to understand. A good entry point for making useful personal connections is comparing what characters in books do, think, or feel to what we might do ourselves. A “Walking in a Character’s Shoes” conference can be just the place to introduce this strategy.

-

Prioritizing: What’s Important to Remember and What’s OK to Forget. Most teachers have met the student who reads a biography of Abraham Lincoln and remembers he had a beard, but forgets that he freed the slaves. While prioritizing is to some extent subjective—after all, if you were doing research on nineteenth century hairstyles, Abe’s beard would be pretty significant—more often than not, there are clues in the text itself that tip us off as to what we are supposed to remember. One of our most important jobs as teachers of reading is to help students learn how to pick up on these text-based cues. Picking up on these text-based cues can be a daunting task for young readers, especially when they have limited knowledge of the subject or genre.

-

What The Author Wants Us To Think About or Feel: Looking for Themes, Lessons, and Big Ideas. One of the criteria most often assessed in tests of reading comprehension for elementary and middle school readers is “Main Idea.” The problem is that most texts of any complexity have multiple big ideas, not just one (Keene 2012). To give students the message that there is one “right answer” is not just intimidating, it’s also misleading. That said, learning to infer (and name) themes in a text is one of the most complicated tasks facing a young reader.

-

Paying Attention to How Things Develop: Tracking Change or the Development of an Idea. Elementary and middle school readers are famous for coming up with one idea and sticking to it, come hell or high water. We need to teach children that while coming up with an idea in the first place is important, readers must allow their thinking to grow and change as they move through a text. This is not easy for students who are just learning to be flexible in their thinking. The object of a “Paying Attention to How Things Develop” conference is to provide a scaffold; we want to give young readers specific work to do to practice tracking an idea as it progresses and grows throughout a text.

-

Compare and Contrast: Noticing What Is Similar and Different. One of the more accessible entry points for deeper thinking about a text is to compare things— the personalities of two different characters in a story, books by the same author, information about sharks in one book to shark facts from another book. The purpose of a “Compare and Contrast” conference is to help students practice critical thinking within, and eventually across, texts

-

Reading Like a Writer: Thinking About How the Author Wrote It. When students notice craft and structure in books, they read like insiders. In the same way that a trained saxophonist hears different things in a Charlie Parker solo than a non-musician, children begin to think more deeply about texts when they learn to read like writers.

♦ ♦ ♦

►To learn more about Reading Projects Reimagined, and to download a sample chapter, visit Heinemann.com.

Dan Feigelson has worked extensively in New York City schools as a teacher, staff developer, curriculum writer, principal, and local superintendent. An early member of the Teachers College Reading and Writing Project, he has led institutes, workshops and lab-sites around the world on the teaching of reading and writing. A regular presenter at national conferences, Dan is the author of Reading Projects Reimagined: Student-Driven Conferences to Deepen Critical Thinking, and Practical Punctuation: Lessons in Rule Making and Rule Breaking in Elementary Writing. He lives in Harlem and Columbia County, New York.

Dan Feigelson has worked extensively in New York City schools as a teacher, staff developer, curriculum writer, principal, and local superintendent. An early member of the Teachers College Reading and Writing Project, he has led institutes, workshops and lab-sites around the world on the teaching of reading and writing. A regular presenter at national conferences, Dan is the author of Reading Projects Reimagined: Student-Driven Conferences to Deepen Critical Thinking, and Practical Punctuation: Lessons in Rule Making and Rule Breaking in Elementary Writing. He lives in Harlem and Columbia County, New York.

Follow Dan on Twitter @danfeigelson.